Adding heat will convert the solid into a liquid with no temperature change. At the melting point, the two phases of a substance, liquid and vapor, have identical free energies and therefore are equally likely to exist. Below the melting point, the solid is the more stable state of the two, whereas above, the liquid form is preferred. The melting point of a substance depends on pressure and is usually specified at standard pressure. When considered as the temperature of the reverse change from liquid to solid, it is called the freezing point or crystallization point.

See also: Melting Point Depression

The first theory explaining the mechanism of melting in bulk was proposed by Lindemann, who used the vibration of atoms in the crystal to explain the melting transition. Solids are similar to liquids in that both are condensed states, with particles far closer together than a gas. The atoms in a solid are tightly bound to each other, either in a regular geometric lattice (crystalline solids, which include metals and ordinary ice) or irregularly (an amorphous solid such as common window glass), typically low in energy. The motion of individual atoms, ions, or molecules in a solid is restricted to vibrational motion about a fixed point. As a solid is heated, its particles vibrate more rapidly as the solid absorbs kinetic energy. At some point, the amplitude of vibration becomes so large that the atoms start to invade the space of their nearest neighbors and disturb them, and the melting process initiates. The melting point is the temperature at which the disruptive vibrations of the particles of the solid overcome the attractive forces operating within the solid.

As with boiling points, a solid’s melting point depends on the strength of those attractive forces. For example, sodium chloride (NaCl) is an ionic compound with many strong ionic bonds, and sodium chloride melts at 801°C. On the other hand, ice (solid H2O) is a molecular compound whose molecules are held together by hydrogen bonds, effectively a strong example of an interaction between two permanent dipoles. Though hydrogen bonds are the strongest of the intermolecular forces, the strength of hydrogen bonds is much less than that of ionic bonds. The melting point of ice is 0 °C.

Covalent bonds often form small collections of better-connected atoms called molecules, which in solids and liquids are bound to other molecules by forces that are often much weaker than the covalent bonds that hold the molecules internally together. Such weak intermolecular bonds give organic molecular substances, such as waxes and oils, their soft bulk character and their low melting points (in liquids, molecules must cease most structured or oriented contact with each other).

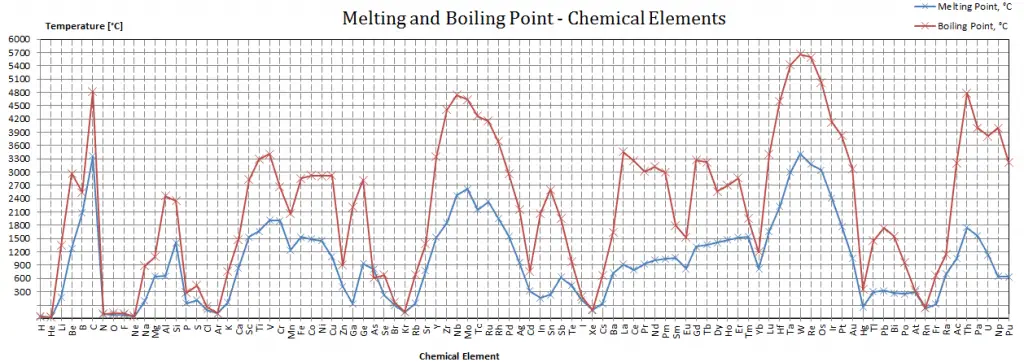

Melting point in the periodic table

For full interactivity, please visit material-properties.org.