Titanium is a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength. Titanium is resistant to corrosion in seawater, aqua regia, and chlorine. In power plants, titanium can be used in surface condensers. The Kroll and Hunter processes extract the metal from its principal mineral ores. Kroll’s process involved a reduction of titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4), first with sodium and calcium and later with magnesium, under an inert gas atmosphere. Pure titanium is stronger than common, low-carbon steels but 45% lighter. It is also twice as strong as weak aluminium alloys but only 60% heavier. The two most useful properties of the metal are corrosion resistance and strength-to-density ratio, the highest of any metallic element. The corrosion resistance of titanium alloys at normal temperatures is unusually high. Titanium’s corrosion resistance is based on forming a stable, protective oxide layer. Although “commercially pure” titanium has acceptable mechanical properties and has been used for orthopedic and dental implants, titanium is alloyed with small amounts of aluminium and vanadium, typically 6% and 4%, respectively, for most applications by weight. This mixture has a solid solubility that varies dramatically with temperature, allowing it to undergo precipitation strengthening.

Titanium is a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength. Titanium is resistant to corrosion in seawater, aqua regia, and chlorine. In power plants, titanium can be used in surface condensers. The Kroll and Hunter processes extract the metal from its principal mineral ores. Kroll’s process involved a reduction of titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4), first with sodium and calcium and later with magnesium, under an inert gas atmosphere. Pure titanium is stronger than common, low-carbon steels but 45% lighter. It is also twice as strong as weak aluminium alloys but only 60% heavier. The two most useful properties of the metal are corrosion resistance and strength-to-density ratio, the highest of any metallic element. The corrosion resistance of titanium alloys at normal temperatures is unusually high. Titanium’s corrosion resistance is based on forming a stable, protective oxide layer. Although “commercially pure” titanium has acceptable mechanical properties and has been used for orthopedic and dental implants, titanium is alloyed with small amounts of aluminium and vanadium, typically 6% and 4%, respectively, for most applications by weight. This mixture has a solid solubility that varies dramatically with temperature, allowing it to undergo precipitation strengthening.

Titanium alloys are metals that contain a mixture of titanium and other chemical elements. Such alloys have high tensile strength and toughness (even at extreme temperatures). They are light in weight, have extraordinary corrosion resistance, and can withstand extreme temperatures.

Strength of Titanium Alloys

In the mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. The strength of materials considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. The strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

The ultimate tensile strength of commercially pure titanium – Grade 2 is about 340 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength of Ti-6Al-4V – Grade 5 titanium alloy is about 1170 MPa.

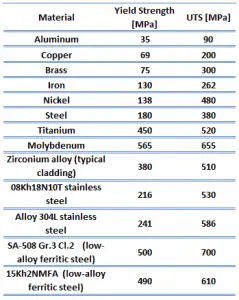

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the specimen preparation, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it depends on other factors, such as the specimen preparation, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels.

Yield Strength

The yield strength of commercially pure titanium – Grade 2 is about 300 MPa.

The yield strength of Ti-6Al-4V – Grade 5 titanium alloy is about 1100 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically. In contrast, the yield point is where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Before the yield point, the material will deform elastically and return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behavior termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for high-strength steel.

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

Young’s modulus of elasticity of commercially pure titanium – Grade 2 is about 105 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity of Ti-6Al-4V – Grade 5 titanium alloy is about 114 GPa.

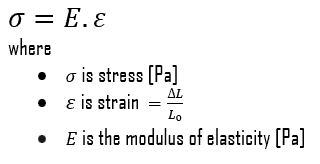

Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on the removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position, and all the atoms are displaced the same amount and maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions, and no permanent deformation occurs. According to Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.