In metallurgy, stainless steel is a steel alloy with at least 10.5% chromium with or without other alloying elements and a maximum of 1.2% carbon by mass. Stainless steels, also known as inox steels or inox from French inoxydable (inoxidizable), are steel alloys that are very well known for their corrosion resistance, which increases with increasing chromium content. Corrosion resistance may also be enhanced by nickel and molybdenum additions. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

In metallurgy, stainless steel is a steel alloy with at least 10.5% chromium with or without other alloying elements and a maximum of 1.2% carbon by mass. Stainless steels, also known as inox steels or inox from French inoxydable (inoxidizable), are steel alloys that are very well known for their corrosion resistance, which increases with increasing chromium content. Corrosion resistance may also be enhanced by nickel and molybdenum additions. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 10.5% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties.

Types of Stainless Steels

Stainless steel is a generic term for a large family of corrosion-resistant alloys containing at least 10.5% chromium and may contain other alloying elements. Numerous grades of stainless steel have varying chromium and molybdenum contents and varying crystallographic structures to suit the environment the alloy must endure. Stainless steels can be divided into five categories:

Stainless steel is a generic term for a large family of corrosion-resistant alloys containing at least 10.5% chromium and may contain other alloying elements. Numerous grades of stainless steel have varying chromium and molybdenum contents and varying crystallographic structures to suit the environment the alloy must endure. Stainless steels can be divided into five categories:

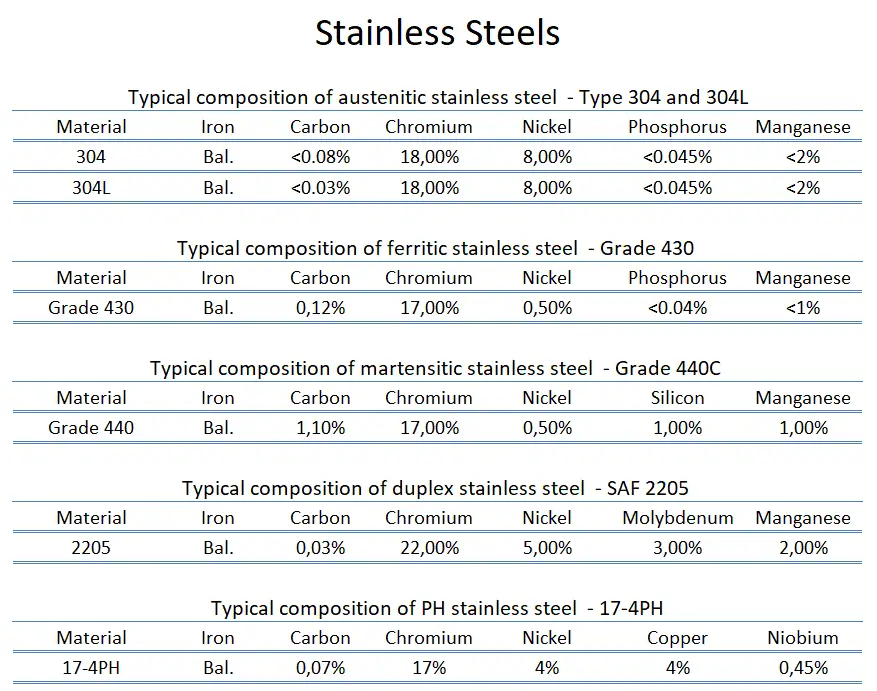

- Ferritic stainless steel. In ferritic stainless steels, carbon is kept to low levels (C<0.08%), and the chromium content can range from 10.50 to 30.00%. They are called ferritic alloys because they contain primarily ferritic microstructures at all temperatures and cannot be hardened through heat treating and quenching. They are classified with AISI 400-series designations. While some ferritic grades contain molybdenum (up to 4.00%), only chromium is present as the main metallic alloying element. They are usually limited to relatively thin sections due to a lack of toughness in welds. Moreover, they have relatively poor high-temperature strength. Ferritic steels are chosen for their resistance to stress corrosion cracking, which makes them an attractive alternative to austenitic stainless steels in applications where chloride-induced SCC is prevalent.

- Austenitic stainless steel. Austenitic stainless steels contain between 16 and 25% Cr and can also contain nitrogen in solution, which contributes to their relatively high corrosion resistance. They are classified with AISI 200- or 300-series designations; the 300-series grades are chromium-nickel alloys, and the 200-series represent a set of compositions in which manganese and/or nitrogen replace some of the nickel. Austenitic stainless steels have the best corrosion resistance of all stainless steels, and they have excellent cryogenic properties and good high-temperature strength. They possess a face-centered cubic (fcc) microstructure that is nonmagnetic and can be easily welded. This austenite crystalline structure is achieved by sufficient additions of the austenite stabilizing elements nickel, manganese, and nitrogen. Austenitic stainless steel is the largest family of stainless steel, making up two-thirds of all stainless steel production. Their yield strength is low (200 to 300MPa), which limits their use for structural and other load-bearing components. They cannot be hardened by heat treatment but have the useful property of being work hardened to high strength levels while retaining a useful level of ductility and toughness. Duplex stainless steels tend to be preferred in such situations because of their high strength and corrosion resistance. The best-known grade is AISI 304 stainless, which contains chromium (between 15% and 20%) and nickel (between 2% and 10.5%) metals as the main non-iron constituents. 304 stainless steel has excellent resistance to a wide range of atmospheric environments and many corrosive media. Cold forming usually characterizes these alloys as ductile, weldable, and hardenable.

- Martensitic stainless steel. Martensitic stainless steels are similar to ferritic steels based on chromium but have higher carbon levels, as high as 1%. They are sometimes classified as low-carbon and high-carbon martensitic stainless steel. They contain 12 to 14% chromium, 0.2 to 1% molybdenum, and no significant amount of nickel. Higher amounts of carbon allow them to be hardened and tempered, much like carbon and low-alloy steels. They have moderate corrosion resistance but are considered hard, strong, and slightly brittle. They are magnetic and can be nondestructively tested using the magnetic particle inspection method, unlike austenitic stainless steel. A common martensitic stainless is AISI 440C, which contains 16 to 18% chromium and 0.95 to 1.2% carbon. Grade 440C stainless steel is used in the following applications: gage blocks, cutlery, ball bearings and races, molds and dies, and knives. As was written, martensitic stainless steels can be hardened and tempered through multiple ways of aging/heat treatment: The metallurgical mechanisms responsible for the martensitic transformations that take place in these stainless alloys during austenitizing and quenching are essentially the same as those that are used to harden lower-alloy-content carbon and alloy steels. The heat treatment typically involves three steps:

Austenitizing, in which the steel is heated to a temperature in the range of 980 – 1050 °C depending on the grades. The austenite is a face-centered cubic phase.

Austenitizing, in which the steel is heated to a temperature in the range of 980 – 1050 °C depending on the grades. The austenite is a face-centered cubic phase.- Quenching. After austenitizing, the steels must be quenched. Martensitic stainless alloys can be quenched using still air, positive pressure vacuum, or interrupted oil quenching. The austenite is transformed into martensite, a hard body-centered tetragonal crystal structure. The martensite is very hard and too brittle for most applications.

- Tempering, i.e., heating to around 500 °C, holding at temperature, then air cooling. Increasing the tempering temperature decreases the yield strength and ultimate tensile strength but increases the elongation and the impact resistance.

- Duplex Stainless Steels. As their name indicates, Duplex stainless steels are a combination of two main alloy types. They have a mixed microstructure of austenite and ferrite, the aim usually being to produce a 50/50 mix, although, in commercial alloys, the ratio may be 40/60. Their corrosion resistance is similar to their austenitic counterparts. Still, their stress-corrosion resistance (especially to chloride stress corrosion cracking), tensile strength, and yield strengths (roughly twice the yield strength of austenitic stainless steels) are generally superior to that of the austenitic grades. In duplex stainless steel, carbon is kept to very low levels (C<0.03%). Chromium content ranges from 21.00 to 26.00%, nickel content ranges from 3.50 to 8.00%, and these alloys may contain molybdenum (up to 4.50%). Toughness and ductility generally fall between those of the austenitic and ferritic grades. Duplex grades are usually divided into three sub-groups based on their corrosion resistance: lean duplex, standard duplex, and superduplex. Superduplex steels have enhanced strength and resistance to all forms of corrosion compared to standard austenitic steels. Common uses include marine applications, petrochemical plants, desalination plants, heat exchangers, and the papermaking industry. Today, the oil and gas industry is the largest user and has pushed for more corrosion-resistant grades, leading to the development of superduplex steels.

- PH Stainless Steels. PH stainless steels (precipitation-hardening) contain around 17% chromium and 4% nickel. These steels can develop very high strength through additions of aluminum, titanium, niobium, vanadium, and/or nitrogen, which form coherent intermetallic precipitates during a heat treatment process referred to as heat aging. As the coherent precipitates form throughout the microstructure, they strain the crystalline lattice and impede the movement of dislocations or defects in a crystal’s lattice. Since dislocations are often the dominant carriers of plasticity, this hardens the material. For example, precipitation-hardened stainless steel 17-4 PH (AISI 630) has an initial microstructure of austenite or martensite. Austenitic grades are converted to martensitic grades through heat treatment (e.g., heat treatment at about 1040 °C followed by quenching) before precipitation hardening. Subsequent aging treatment at about 475 °C precipitates Nb and Cu-rich phases, increasing the strength to above 1000 MPa yield strength. Unlike austenitic alloys, heat treatment strengthens PH steel to levels higher than martensitic alloys. Precipitation-hardening stainless steels are designated by the AISI 600-series. Of all the available stainless grades, they generally offer the greatest combination of high strength and excellent toughness and corrosion resistance. They are as corrosion-resistant as austenitic grades. Common uses are in the aerospace and some other high-technology industries.

Alloying Agents in Stainless Steels

Pure iron is too soft to be used for structure, but adding small quantities of other elements (carbon, manganese, or silicon, for instance) greatly increases its mechanical strength. Alloys are usually stronger than pure metals, although they generally offer reduced electrical and thermal conductivity. Strength is the most important criterion by which many structural materials are judged. Therefore, alloys are used for engineering construction. The synergistic effect of alloying elements and heat treatment produces various microstructures and properties.

- Carbon. Carbon is a non-metallic element, an important alloying element in all ferrous metal-based materials. Carbon is always present in metallic alloys, i.e., in all grades of stainless steel and heat-resistant alloys. Carbon is a very strong austenitizing and increases the strength of steel. It is the principal hardening element essential to forming cementite, Fe3C, pearlite, spheroidite, and iron-carbon martensite. Adding a small amount of non-metallic carbon to iron trades its great ductility for greater strength. Suppose it combines chromium as a separate constituent (chromium carbide). In that case, it may have a detrimental effect on corrosion resistance by removing some of the chromium from the solid solution in the alloy and, consequently, reducing the amount of chromium available to ensure corrosion resistance.

- Chromium. Chromium increases hardness, strength, and corrosion resistance. The strengthening effect of forming stable metal carbides at the grain boundaries and the strong increase in corrosion resistance made chromium an important alloying material for steel. The resistance of these metallic alloys to the chemical effects of corrosive agents is based on passivation. For passivation to occur and remain stable, the Fe-Cr alloy must have a minimum chromium content of about 11% by weight, above which passivity can occur and below is impossible. Chromium can be used as a hardening element and is frequently used with a toughening element such as nickel to produce superior mechanical properties. At higher temperatures, chromium contributes to increased strength. The high-speed tool steels contain between 3 and 5% chromium, and it is ordinarily used for applications of this nature in conjunction with molybdenum.

- Nickel. Nickel is one of the most common alloying elements. About 65% of nickel production is used in stainless steel. Because nickel does not form any carbide compounds in steel, it remains in solution in the ferrite, thus strengthening and toughening the ferrite phase. Nickel steels are easily heat treated because nickel lowers the critical cooling rate. Nickel-based alloys (e.g., Fe-Cr-Ni(Mo) alloys) exhibit excellent ductility and toughness, even at high strength levels and these properties are retained up to low temperatures. Nickel also reduces thermal expansion for better dimensional stability. Nickel is the base element for superalloys, a group of nickel, iron-nickel, and cobalt alloys used in jet engines. These metals have excellent resistance to thermal creep deformation and retain their stiffness, strength, toughness, and dimensional stability at temperatures much higher than the other aerospace structural materials.

- Molybdenum. In small quantities in stainless steel, molybdenum increases hardenability and strength, particularly at high temperatures. The high melting point of molybdenum makes it important for giving strength to steel and other metallic alloys at high temperatures. Molybdenum is unique in the extent to which it increases steel’s high-temperature tensile and creeps strengths. It retards the transformation of austenite to pearlite far more than the transformation of austenite to bainite; thus, bainite may be produced by continuous cooling of molybdenum-containing steels.

- Vanadium. Vanadium is generally added to steel to inhibit grain growth during heat treatment. Controlling grain growth improves the strength and toughness of hardened and tempered steels.

- Tungsten. Produces stable carbides and refines grain size to increase hardness, particularly at high temperatures. Tungsten is used extensively in high-speed tool steels and has been proposed as a substitute for molybdenum in reduced-activation ferritic steels for nuclear applications.

Strength of Stainless Steels

In the mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. The strength of materials considers the relationship between the external loads applied to a material and the resulting deformation or change in material dimensions. The strength of a material is its ability to withstand this applied load without failure or plastic deformation.

Ultimate Tensile Strength

The ultimate tensile strength of stainless steel – type 304 is 515 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength of stainless steel – type 304L is 485 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength of ferritic stainless steel – Grade 430 is 480 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength of martensitic stainless steel – Grade 440C is 760 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength of duplex stainless steel – SAF 2205 is 620 MPa.

The ultimate tensile strength of precipitation hardening steel – 17-4PH stainless steel depends on the heat treatment process, but it is about 1000 MPa.

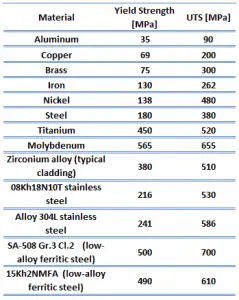

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress sustained by a structure in tension. Ultimate tensile strength is often shortened to “tensile strength” or “the ultimate.” If this stress is applied and maintained, a fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60 percent more than the yield for some types of metals). When a ductile material reaches its ultimate strength, it experiences necking where the cross-sectional area reduces locally. The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength. Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after achieving the ultimate strength. It is an intensive property; therefore, its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for aluminum to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steel.

Yield Strength

The yield strength of stainless steel – type 304 is 205 MPa.

The yield strength of stainless steel – type 304L is 170 MPa.

The yield strength of ferritic stainless steel – Grade 430 is 310 MPa.

The yield strength of martensitic stainless steel – Grade 440C is 450 MPa.

The yield strength of duplex stainless steel – SAF 2205 is 440 MPa.

The yield strength of precipitation hardening steels – 17-4PH stainless steel depends on heat treatment, but it is about 850 MPa.

The yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning plastic behavior. Yield strength or yield stress is the material property defined as the stress at which a material begins to deform plastically. In contrast, the yield point is the point where nonlinear (elastic + plastic) deformation begins. Before the yield point, the material will deform elastically and return to its original shape when the applied stress is removed. Once the yield point is passed, some fraction of the deformation will be permanent and non-reversible. Some steels and other materials exhibit a behavior termed a yield point phenomenon. Yield strengths vary from 35 MPa for low-strength aluminum to greater than 1400 MPa for high-strength steel.

Young’s Modulus of Elasticity

Young’s modulus of elasticity stainless steel – type 304 and 304L is 193 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity of ferritic stainless steel – Grade 430 is 220 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity of martensitic stainless steel – Grade 440C is 200 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity of duplex stainless steel – SAF 2205 is 200 GPa.

Young’s modulus of elasticity of precipitation hardening steel – 17-4PH stainless steel is 200 GPa.

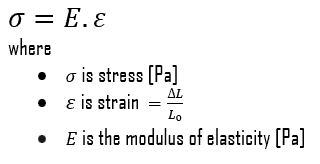

Young’s modulus of elasticity is the elastic modulus for tensile and compressive stress in the linear elasticity regime of a uniaxial deformation and is usually assessed by tensile tests. Up to limiting stress, a body will be able to recover its dimensions on the removal of the load. The applied stresses cause the atoms in a crystal to move from their equilibrium position, and all the atoms are displaced the same amount and maintain their relative geometry. When the stresses are removed, all the atoms return to their original positions, and no permanent deformation occurs. According to Hooke’s law, the stress is proportional to the strain (in the elastic region), and the slope is Young’s modulus. Young’s modulus is equal to the longitudinal stress divided by the strain.