In general, semiconductors are inorganic or organic materials that can control their conduction depending on chemical structure, temperature, illumination, and the presence of dopants. The name semiconductor comes from the fact that these materials have electrical conductivity between a metal, like copper, gold, etc., and an insulator, like glass. They have an energy gap of less than 4eV (about 1eV). In solid-state physics, this energy gap or band gap is an energy range between the valence band and conduction band where electron states are forbidden. In contrast to conductors, semiconductors’ electrons must obtain energy (e.g., from ionizing radiation) to cross the band gap and reach the conduction band. Properties of semiconductors are determined by the energy gap between valence and conduction bands.

Germanium as Semiconductor

Germanium is a chemical element with the atomic number 32, which means there are 32 protons and 32 electrons in the atomic structure. The chemical symbol for Germanium is Ge. Germanium is a lustrous, hard, grayish-white metalloid in the carbon group, chemically similar to its group neighbors, tin and silicon. Pure germanium is a semiconductor with an appearance similar to elemental silicon. Germanium is widely used for gamma-ray spectroscopy. In gamma spectroscopy, germanium is preferred due to its atomic number being much higher than silicon, increasing the probability of gamma-ray interaction. Germanium is more used than silicon for radiation detection because the average energy necessary to create an electron-hole pair is 3.6 eV for silicon and 2.9 eV for germanium, which provides the latter a better resolution in energy. On the other hand, germanium has a small band gap energy (Egap = 0.67 eV), which requires operating the detector at cryogenic temperatures.

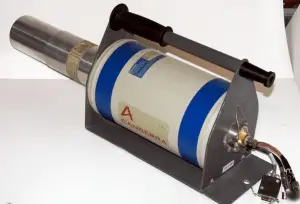

Germanium-based Semiconductor Detectors

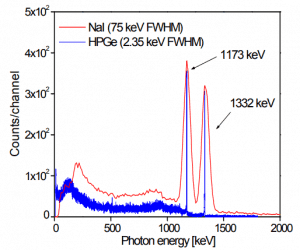

Germanium-based semiconductor detectors are most commonly used where a very good energy resolution is required, especially for gamma spectroscopy as well as x-ray spectroscopy. In gamma spectroscopy, germanium is preferred due to its atomic number being much higher than silicon, increasing the probability of gamma-ray interaction. Moreover, germanium has lower average energy necessary to create an electron-hole pair, which is 3.6 eV for silicon and 2.9 eV for germanium. This also provides the latter with a better resolution in energy. A large, clean, and almost perfect germanium semiconductor is ideal as a counter to radioactivity. However, making large crystals with sufficient purity is difficult and expensive. While silicon-based detectors cannot be thicker than a few millimeters, germanium can have a depleted, sensitive thickness of centimeters. It, therefore, can be used as a total absorption detector for gamma rays up to a few MeV.

On the other hand, to achieve maximum efficiency, the detectors must operate at very low temperatures of liquid nitrogen (-196°C) because the noise caused by thermal excitation is very high at room temperatures.

Since germanium detectors produce the highest resolution commonly available today, they are used to measure radiation in a variety of applications, including personnel and environmental monitoring for radioactive contamination, medical applications, radiometric assay, nuclear security, and nuclear plant safety.