Personal dosimetry is a key part of radiation dosimetry. Personal dosimetry is used primarily (but not exclusively) to determine doses for individuals exposed to radiation related to their work activities. These doses are usually measured by devices known as personal dosimeters. Dosimeters usually record a dose, the absorbed radiation energy measured in grays (Gy), or the equivalent dose measured in sieverts (Sv). A personal dosimeter is a dosimeter worn at the body’s surface by the person being monitored and records the radiation dose received. Personal dosimetry techniques vary and depend partly on whether the source of radiation is outside the body (external) or taken into the body (internal). Personal dosimeters are used to measure external radiation exposures. Internal exposures are typically monitored by measuring the presence of nuclear substances in the body or by measuring nuclear substances excreted by the body.

Commercially available dosimeters range from low-cost, passive devices that store personnel dose information for later readout to more expensive, battery-operated devices that display immediate dose and dose rate information (typically an electronic personal dosimeter). Readout method, dose measurement range, size, weight, and price are important selection factors.

There are two kinds of dosimeters:

- Passive Dosimeters. Commonly used passive dosimeters are the Thermo Luminescent Dosimeter (TLD) and the film badge. A passive dosimeter produces a radiation-induced signal stored in the device, and the dosimeter is then processed, and the output is analyzed.

- Active Dosimeters. You can use an active dosimeter, typically an electronic personal dosimeter (EPD), to get a real-time exposure value. An active dosimeter produces a radiation-induced signal and displays a direct reading of the detected dose or dose rate in real-time.

The passive and the active dosimeters are often used together to complement each other. Dosimeters must be worn on a position of the body representative of its exposure to estimate effective doses, typically between the waist and the neck, on the front of the torso, facing the radioactive source. Dosimeters are usually worn outside clothing, around the chest or torso to represent dose to the “whole body.” Dosimeters may also be worn on the extremities or near the eye to measure equivalent doses to these tissues.

The personal dosimeters in use today are not absolute but reference instruments, meaning they must be periodically calibrated. When a reference dosimeter is calibrated, a calibration factor can be determined. This calibration factor relates the exposure quantity to the reported dose. The validity of the calibration is demonstrated by maintaining the traceability of the source used to calibrate the dosimeter. The traceability is achieved by comparison of the source with a “primary standard” at a reference calibration center. In monitoring individuals, the values of these operational quantities are taken as a sufficiently precise assessment of effective dose and skin dose, respectively, if their values are below the protection limits.

Example – Electronic Personal Dosimeter

An electronic personal dosimeter is a modern dosimeter that can give a continuous readout of cumulative dose and current dose rate and warn the person wearing it when a specified dose rate or a cumulative dose is exceeded. EPDs are especially useful in high-dose areas where the residence time of the wearer is limited due to dose constraints.

Types of EPDs

EPDs are battery-powered, and most use either a small Geiger-Mueller (GM) tube or a semiconductor in which ionizing radiation releases charges resulting in measurable electric current.

- G-M counter. A Geiger counter consists of a Geiger-Müller tube (the sensing element which detects the radiation) and the processing electronics, which displays the result. G-M counters are mainly used for portable instrumentation due to their sensitivity, simple counting circuit, and ability to detect low-level radiation. Because of the large avalanche induced by any ionization, a Geiger counter takes a long time (about 1 ms) to recover between successive pulses. Therefore, Geiger counters cannot measure high radiation rates due to the “dead time” of the tube.

- Semiconductor Detector. Semiconductor detectors are based on ionization in a solid (e.g., silicon) and include different types of solid-state devices with two terminals called diodes. For example, a silicon diode has a p-i-n structure in which the intrinsic (i) region is sensitive to ionizing radiation, particularly X-rays and gamma rays. Under reverse bias, an electric field extends across the intrinsic or depleted region. In this case, a negative voltage is applied to the p-side and positive to the second one. Holes in the p-region are attracted from the junction towards the p contact and similarly for electrons and the n contact.

- Scintillation Detector. Some EPDs use a scintillating crystal such as sodium iodide (NaI) or cesium iodide (CsI) with a photodiode or photomultiplier tube to measure photons released by radiation.

Characteristics of EPDs

The electronic personal dosimeter, EPD, can display a direct reading of the detected dose or dose rate in real-time. Electronic dosimeters may be used as supplemental dosimeters and primary dosimeters. The passive and electronic personal dosimeters are often used together to complement each other. Dosimeters must be worn on a position of the body representative of its exposure to estimate effective doses, typically between the waist and the neck, on the front of the torso, facing the radioactive source. Dosimeters are usually worn outside clothing, around the chest or torso to represent dose to the “whole body.” Dosimeters may also be worn on the extremities or near the eye to measure equivalent doses to these tissues.

The dosimeter can be reset, usually after taking a reading for record purposes, and thereby re-used multiple times. The EPDs have a top-mounted display to make them easily read when clipped to your breast pocket. The digital display gives dose and dose rate information, usually in mSv and mSv/h. The EPD has a dose rate alarm and a dose alarm. These alarms are programmable, and different alarms can be set for different activities.

For example:

- dose rate alarm at 100 μSv/h,

- dose alarm: 100 μSv.

If an alarm set point is reached, the relevant display flashes along with a red light, and quite a piercing noise is generated. You can clear the dose rate alarm by retreating to a lower radiation field, but you cannot clear the dose alarm until you get to an EPD reader. EPDs can also give a bleep for every 1 or 10 μSv they register, giving you an audible indication of the radiation fields. Some EPDs have wireless communication capabilities. EPDs can measure a wide radiation dose range from routine (μSv) levels to emergency levels (hundreds mSv or units of Sieverts) with high precision. They may display the exposure rate and accumulated exposure values. Of the dosimeter technologies, electronic personal dosimeters are generally the most expensive, largest in size, and the most versatile.

DMC 3000 – Mirion Technologies Inc.

The DMC 3000 is an electronic radiation dosimeter, EPD, that provides dose and ambient dose rate readings for deep dose equivalent Hp(10). It is one of the most used EPDs on the market. It uses a Si chip detector with a gamma sensitivity of 180 cps/R/h. This electronic personal dosimeter has the following characteristics:

- Energy response (X-ray and gamma) from 15 keV to 7 MeV.

- Dose measurement display range: between 1 μSv and 10 Sv.

- Rate measurement display range: between 10 μSv/hr and 10 Sv/h.

The device measures 3.3 x 1.9 x 0.7 inches and has options for being clipped to a pocket, belt, or lanyard. It is powered with rechargeable or AAA batteries with a battery life of up to 2,500 hours of continuous use. Audible and visual indicators signal a low battery condition. The device has a backlit, eight-digit LCD display, two-button navigation, and visual LED, audible and vibrating alarm indicators. Calibration is expected to last 9 months under routine use and 2 years in storage. Data is stored in nonvolatile memory. The operating range for the dosimeter is from 14°F to 122°F and up to 90 percent relative humidity. It is drop tested to 1.5 meters. The DMC 3000 has optional external modules that expand the device’s detection and communication capabilities. These include a beta module that provides Hp(0,07) for beta radiation measurement; a neutron module that provides Hp(10) neutron radiation measurement; and a telemetry module that allows transmission of data to an external station.

See also: The Radiation Dosimeters for Response and Recovery Market Survey Report. National Urban Security Technology Laboratory. SAVER-T-MSR-4. <available from: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Radiation-Dosimeters-Response-Recovery-MSR_0616-508_0.pdf>.

Example – Neutron TLD

A thermoluminescent dosimeter, abbreviated as TLD, is a passive radiation dosimeter, that measures ionizing radiation exposure by measuring the intensity of visible light emitted from a sensitive crystal in the detector when the crystal is heated. The intensity of light emitted is measured by the TLD reader, depending on the radiation exposure. Thermoluminescent dosimeters were invented in 1954 by Professor Farrington Daniels of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. TLD dosimeters apply to situations where real-time information is not needed. Still, precise accumulated dose monitoring records are desired for comparison to field measurements or for assessing the potential for long-term health effects. In dosimetry, the quartz fiber and film badge types are superseded by TLDs and EPDs (Electronic Personal Dosimeter).

Neutron Thermoluminescent Dosimeter – Neutron TLD

The personnel neutron dosimetry continues to be one of the problems in the field of radiation protection, as no single method provides the combination of energy response, sensitivity, orientation dependence characteristics, and accuracy necessary to meet the needs of a personnel dosimeter.

The most commonly used personnel neutron dosimeters for radiation protection purposes are thermoluminescent dosimeters and albedo dosimeters. Both are based on this phenomenon – thermoluminescence. For this purpose, lithium fluoride (LiF) as sensitive material (chip) is widely used. Lithium fluoride TLD is used for gamma and neutron exposure (indirectly, using the Li-6 (n, alpha)) nuclear reaction. Small crystals of LiF (lithium fluoride) are the most common TLD dosimeters since they have the same absorption properties as soft tissue. Lithium has two stable isotopes, lithium-6 (7.4 %) and lithium-7 (92.6 %). Li-6 is the isotope sensitive to neutrons. LiF crystal dosimeters may be enriched in lithium-6 to enhance the lithium-6 (n, alpha) nuclear reaction to record neutrons. The efficiency of the detector depends on the energy of the neutrons. Because the interaction of neutrons with any element is highly dependent on energy, making a dosimeter independent of the energy of neutrons is very difficult. LiF dosimeters are mostly utilized, containing different percentages of lithium-6 to separate thermal neutrons and photons. LiF chip enriched in lithium-6, which is very sensitive to thermal neutrons, and LiF chip containing very little lithium-6, which has a negligible neutron response.

The principle of neutron TLDs is then similar to gamma radiation TLDs. In the LiF chip, there are impurities (e.g., manganese or magnesium), which produce trap states for energetic electrons. The impurity causes traps in the crystalline lattice where electrons are held following irradiation (to alpha radiation). When the crystal is warmed, the trapped electrons are released and light is emitted. The amount of light is related to the dose of radiation received by the crystal.

Thermoluminiscent Albedo Neutron Dosimeter

Albedo neutron dosimetry is based on the human body’s effect of moderation and backscattering of neutrons. Albedo, the Latin word for “whiteness,” is defined by Lambert as the fraction of the incident light reflected diffusely by a surface. Moderation and backscattering of neutrons by the human body create a neutron flux at the body surface in the thermal and intermediate energy range. These backscattered neutrons, called albedo neutrons, can be detected by a dosimeter (usually a LiF TLD chip) placed on the body, designed to detect thermal neutrons. Albedo dosimeters are the only dosimeters that can measure doses due to neutrons over the whole range of energies. Usually, two types of lithium fluoride are used to separate doses contributed by gamma-rays and neutrons. LiF chip enriched in lithium-6, which is very sensitive to thermal neutrons, and LiF chip containing very little lithium-6, which has a negligible neutron response.

Radiation Dose Measuring and Monitoring

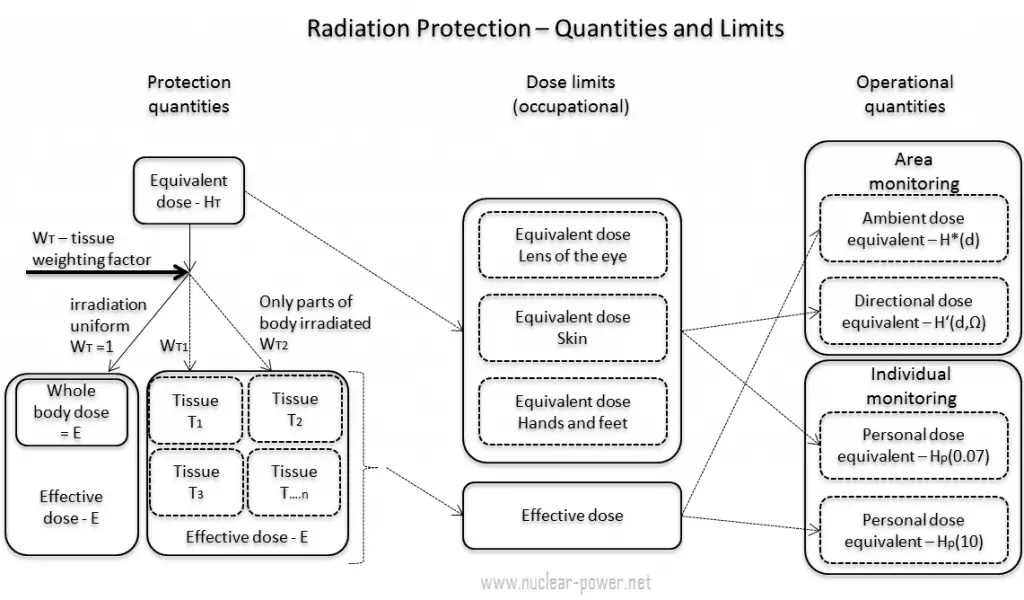

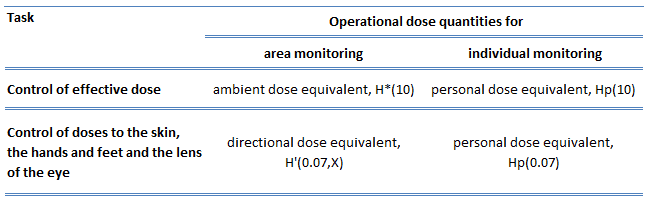

In previous chapters, we described the equivalent dose and the effective dose. But these doses are not directly measurable. For this purpose, the ICRP has introduced and defined a set of operational quantities that can be measured and intended to provide a reasonable estimate for the protection quantities. These quantities aim to provide a conservative estimate for the value of the protection quantities related to an exposure avoiding both underestimation and too much overestimation.

Numerical links between these quantities are represented by conversion coefficients, which are defined for a reference person. An internationally agreed set of conversion coefficients must be available for general use in radiological protection practice for occupational exposures and exposures of the public. Computational phantoms are used for dose assessment in various radiation fields to calculate conversion coefficients for external exposure. Biokinetic models for radionuclides, reference physiological data, and computational phantoms are used for calculating dose coefficients from intakes of radionuclides.

A set of evaluated data of conversion coefficients for protection and operational quantities for external exposure to a mono-energetic photon, neutron, and electron radiation under specific irradiation conditions is published in reports (ICRP, 1996b, ICRU, 1997).

In general, the ICRP defines operational quantities for the area and individual monitoring of external exposures. The operational quantities for area monitoring are:

In general, the ICRP defines operational quantities for the area and individual monitoring of external exposures. The operational quantities for area monitoring are:

- Ambient dose equivalent, H*(10). The ambient dose equivalent is an operational quantity for area monitoring of strongly penetrating radiation.

- Directional dose equivalent, H’ (d, Ω). The directional dose equivalent is an operational quantity for area monitoring weakly penetrating radiation.

The operational quantities for individual monitoring are:

- Personal dose equivalent, Hp(0.07). The Hp(0.07) dose equivalent is an operational quantity for individual monitoring to assess the dose to the skin, hands, and feet.

- Personal dose equivalent, Hp(10). The Hp(10) dose equivalent is an operational quantity for individual monitoring to assess the effective dose.

Special Reference: ICRP, 2007. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 103. Ann. ICRP 37 (2-4).

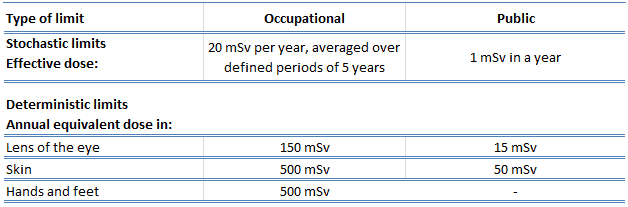

Dose Limits

See also: Dose Limits

Dose limits are split into two groups, the public and occupationally exposed workers. According to ICRP, occupational exposure refers to all exposure incurred by workers in the course of their work, except for

- excluded exposures and exposures from exempt activities involving radiation or exempt sources

- any medical exposure

- the normal local natural background radiation.

The following table summarizes dose limits for occupationally exposed workers and the public:

Source of data: ICRP, 2007. The 2007 Recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 103. Ann. ICRP 37 (2-4).

According to the recommendation of the ICRP in its statement on tissue reactions of 21. April 2011, the equivalent dose limit for the eye lens for occupational exposure in planned exposure situations was reduced from 150 mSv/year to 20 mSv/year, averaged over defined periods of 5 years, with no annual dose in a single year exceeding 50 mSv.

Limits on effective dose are for the sum of the relevant effective doses from external exposure in the specified period and the committed effective dose from intakes of radionuclides in the same period. For adults, the committed effective dose is computed for 50 years after intake, whereas for children, it is computed for the period up to 70 years. The effective whole-body dose limit of 20 mSv is an average value over five years, and the real limit is 100 mSv in 5 years, with not more than 50 mSv in any year.