Banana equivalent dose, BED, is an informal dose quantity of ionizing radiation exposure. Banana equivalent dose is intended as a general educational example to compare a dose of radioactivity to the dose one is exposed to by eating one average-sized banana. One BED is often correlated to 10-7 Sievert (0.1 µSv).

Bananas contain significantly high potassium concentrations, which are vital for the functioning of all living cells. The transfer of potassium ions through nerve cell membranes is necessary for normal nerve transmission. But natural potassium also contains a radioactive isotope potassium-40 (0.012%). Potassium-40 is a radioactive isotope of potassium that has a very long half-life of 1.251×109 years and undergoes both types of beta decay.

- About 89.28% of the time (10.72% is by electron capture), it decays to calcium-40 with the emission of a beta particle (β−, an electron) with a maximum energy of 1.33 MeV and an antineutrino, which is an antiparticle to the neutrino.

- Very rarely (0.001% of the time) will it decay to Ar-40 by emitting a positron (β+) and a neutrino.

One BED is often correlated to 10-7 Sievert (0.1 µSv). The radiation exposure from consuming a banana is approximately 1% of the average daily exposure to radiation, which is 100 banana equivalent doses (BED). A chest CT scan delivers 58,000 BED (5.8 mSv). A lethal dose, which kills a human with a 50% risk within 30 days (LD50/30) of radiation, is approximately 50,000,000 BED (5000 mSv). However, this dose is not cumulative in practice, as the principal radioactive component is excreted to maintain metabolic equilibrium. Moreover, there is also a problem with the collective dose.

The BED is only meant to inform the public about the existence of very low levels of natural radioactivity within a natural food. It is not a formally adopted dose measurement.

Radiation from Bananas – Is it dangerous?

We must emphasize that eating bananas, working as an airline flight crew, or living in locations, increases your annual dose rate. But it does not mean that it must be dangerous. In each case, the intensity of radiation also matters. It is very similar to heat from a fire (less energetic radiation). If you are too close, the intensity of heat radiation is high, and you can get burned. If you are at the right distance, you can withstand it without any problems, and it is comfortable. If you are too far from a heat source, the insufficiency of heat can also hurt you. In a certain sense, this analogy can be applied to radiation also from radiation sources.

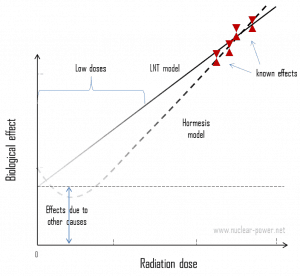

In the case of internal radiation, we are usually talking about so-called “low doses.” A low dose means additional small doses comparable to the normal background radiation (10 µSv = average daily dose received from natural background). The doses are very, very low, and therefore the probability of cancer induction could be almost negligible. Secondly, and this is crucial, the truth about low-dose radiation health effects still needs to be found. It is unknown whether these low doses of radiation are detrimental or beneficial (and where is the threshold). Government and regulatory bodies assume an LNT model instead of a threshold or hormesis not because it is the more scientifically convincing but because it is, the more conservative estimate. The problem with this model is that it neglects many defense biological processes that may be crucial at low doses. The research during the last two decades is very interesting and shows that small doses of radiation given at a low dose rate stimulate the defense mechanisms. Therefore the LNT model is not universally accepted, with some proposing an adaptive dose-response relationship where low doses are protective, and high doses are detrimental. Many studies have contradicted the LNT model, and many have shown adaptive response to low dose radiation resulting in reduced mutations and cancers. This phenomenon is known as radiation hormesis.