If the radiation source is inside our body, we say it is internal exposure. The intake of radioactive material can occur through various pathways, such as ingesting radioactive contamination in food or liquids, and protection from internal exposure is more complicated. Most radionuclides will give you much more radiation dose if they can somehow enter your body than they would if they remained outside.

As was written, it is crucial whether we are exposed to radiation from external sources or internal sources. This is similar to other dangerous substances. Internal exposure is more dangerous than external exposure since we carry the radiation source inside our bodies, and we cannot use any of the radiation protection principles (time, distance, shielding). The intake of radioactive material can occur through various pathways such as ingesting radioactive contamination in food or liquids, inhalation of radioactive gases, or through intact or wounded skin. In this place, we have to distinguish between radiation and contamination. Radioactive contamination consists of radioactive material that generates ionizing radiation. It is the source of radiation, not radiation itself. Anytime radioactive material is not in a sealed radioactive source container and might be spread onto other objects, radioactive contamination is possible. For example, radioiodine, iodine-131, is an important radioisotope of iodine. Radioiodine plays a major role as a radioactive isotope present in nuclear fission products. It is a major contributor to health hazards when released into the atmosphere during an accident. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8.02 days. The target tissue for radioiodine exposure is the thyroid gland. The external beta and gamma dose from radioiodine present in the air is quite negligible compared to the committed dose to the thyroid resulting from breathing this air.

Airborne Contamination

Airborne contamination is particularly important in nuclear power plants, which must be monitored. Contaminants can become airborne, especially during reactor top head removal, reactor refueling, and during manipulations within the spent fuel pool. The air can be contaminated with radioactive isotopes, especially particulate form, which poses a particular inhalation hazard. This contamination consists of various fission and activation products that enter the air in gaseous, vapor, or particulate form. There are four types of airborne contamination in nuclear power plants, namely:

- Particulates. Particulate activity is an internal hazard because it can be inhaled. Transportable particulate material taken into the respiratory system will enter the bloodstream and be carried to all body parts. Non-transportable particulates will stay in the lungs with a certain biological half-life. For example, Sr-90, Ra-226, and Pu-239 are radionuclides known as bone-seeking radionuclides. These radionuclides have long biological half-lives and are serious internal hazards. Once deposited in bone, they remain unchanged in amount during the individual’s lifetime. The continued action of the emitted alpha particles can cause significant injury. Over many years, they deposit all their energy in a tiny volume of tissue because the range of the alpha particles is very short.

- Noble gases. Radioactive noble gases, such as xenon-133, xenon-135, and krypton-85, are present in reactor coolant, especially when fuel leakages are present. As they appear in coolant, they become airborne, and they can be inhaled and exhaled right after inhaling because the body does not react chemically with them. If workers work in a noble gas cloud, their external dose is about 1000 times greater than the internal dose. Because of this, we are only concerned about the external beta and gamma dose rates.

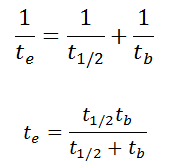

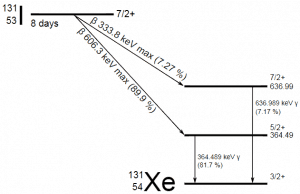

Radioiodine. Radioiodine, iodine-131, is an important radioisotope of iodine. Radioiodine plays a major role as a radioactive isotope present in nuclear fission products. It is a major contributor to health hazards when released into the atmosphere during an accident. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8.02 days. The target tissue for radioiodine exposure is the thyroid gland. The external beta and gamma dose from radioiodine present in the air is quite negligible compared to the committed dose to the thyroid resulting from breathing this air. The biological half-life for iodine inside the human body is about 80 days (according to ICRP). Iodine in food is absorbed by the body and preferentially concentrated in the thyroid, where it is needed for the functioning of that gland. When 131I is present in high levels in the environment from radioactive fallout, it can be absorbed through contaminated food and accumulate in the thyroid. 131I decays with a half-life of 8.02 days with beta particle and gamma emissions. As it decays, it may cause damage to the thyroid. The primary risk from exposure to high levels of 131I is the chance of occurrence of radiogenic thyroid cancer in later life. For 131I, ICRP has calculated that if you inhale 1 x 106 Bq, you will receive a thyroid dose of HT = 400 mSv (and a weighted whole-body dose of 20 mSv).

Radioiodine. Radioiodine, iodine-131, is an important radioisotope of iodine. Radioiodine plays a major role as a radioactive isotope present in nuclear fission products. It is a major contributor to health hazards when released into the atmosphere during an accident. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8.02 days. The target tissue for radioiodine exposure is the thyroid gland. The external beta and gamma dose from radioiodine present in the air is quite negligible compared to the committed dose to the thyroid resulting from breathing this air. The biological half-life for iodine inside the human body is about 80 days (according to ICRP). Iodine in food is absorbed by the body and preferentially concentrated in the thyroid, where it is needed for the functioning of that gland. When 131I is present in high levels in the environment from radioactive fallout, it can be absorbed through contaminated food and accumulate in the thyroid. 131I decays with a half-life of 8.02 days with beta particle and gamma emissions. As it decays, it may cause damage to the thyroid. The primary risk from exposure to high levels of 131I is the chance of occurrence of radiogenic thyroid cancer in later life. For 131I, ICRP has calculated that if you inhale 1 x 106 Bq, you will receive a thyroid dose of HT = 400 mSv (and a weighted whole-body dose of 20 mSv).- Tritium. Tritium is a byproduct of nuclear reactors. The most important source (due to releases of tritiated water) of tritium in nuclear power plants stems from the boric acid, commonly used as a chemical shim to compensate for an excess of initial reactivity. Note that tritium emits low-energy beta particles with a short range in body tissues and, therefore, poses a risk to health as a result of internal exposure only following ingestion in drinking water or food, or inhalation or absorption through the skin. The tritium taken into the body is uniformly distributed among all soft tissues. According to the ICRP, a biological half-time of tritium is 10 days for HTO and 40 days for OBT (organically bound tritium) formed from HTO in the body of adults. As a result, for an intake of 1 x 109 Bq of tritium (HTO), an individual will get a whole-body dose of 20 mSv (equal to the intake of 1 x 106 Bq of 131I). While for PWRs, tritium poses a minor risk to health, for heavy water reactors, it contributes significantly to a collective dose of plant workers. Note that “Air saturated with moderator water at 35°C can give 3 000 mSv/h of tritium to an unprotected worker (See also: J.U.Burnham. Radiation Protection). The best protection from tritium can be achieved using an air-supplied respirator. Tritium cartridge respirators protect workers only by a factor of 3. The only way to reduce skin absorption is by wearing plastics. In PHWR power plants, workers must wear plastics for work in atmospheres containing more than 500 μSv/h.