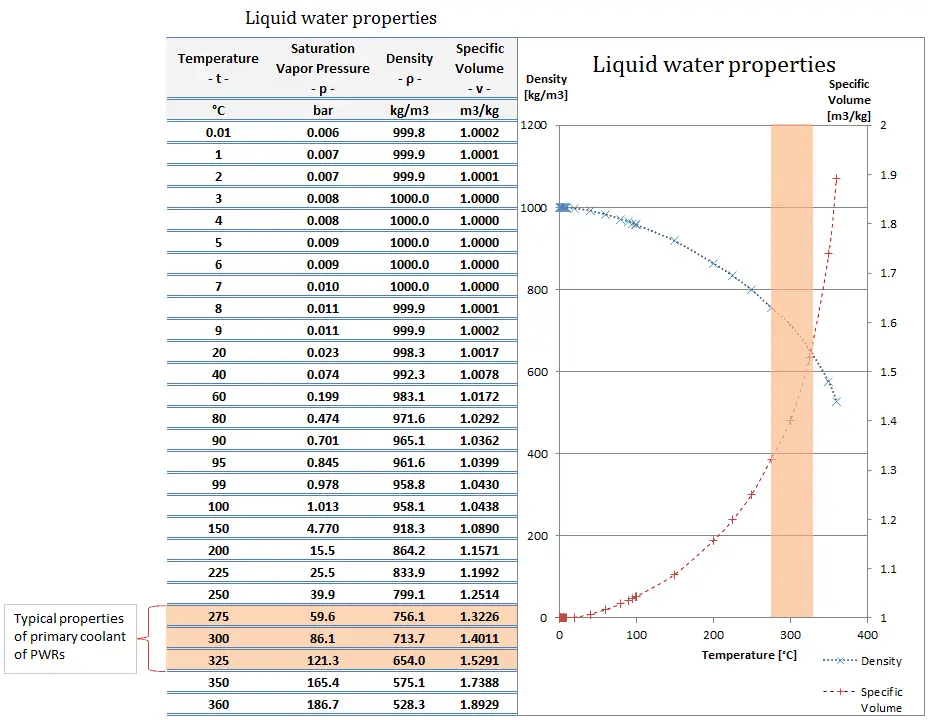

Density of Water – H2O

Pure water has its highest density of 1000 kg/m3 at a temperature of 3.98oC (39.2oF). Water differs from most liquids in that it becomes less dense as it freezes. It has a maximum density of 3.98 °C (1000 kg/m3), whereas the density of ice is 917 kg/m3. It differs by about 9%, and therefore ice floats on liquid water. It must be noted, the change in density is not linear with temperature because the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient for water is not constant over the temperature range. The density of water (1 gram per cubic centimeter) was originally used to define the gram. The density (⍴) of a substance is the reciprocal of its specific volume (ν).

ρ = m/V = 1/ν

The specific volume (ν) of a substance is the total volume (V) of that substance divided by the total mass (m) of that substance (volume per unit mass). It has units of cubic meters per kilogram (m3/kg).

Density of Steam

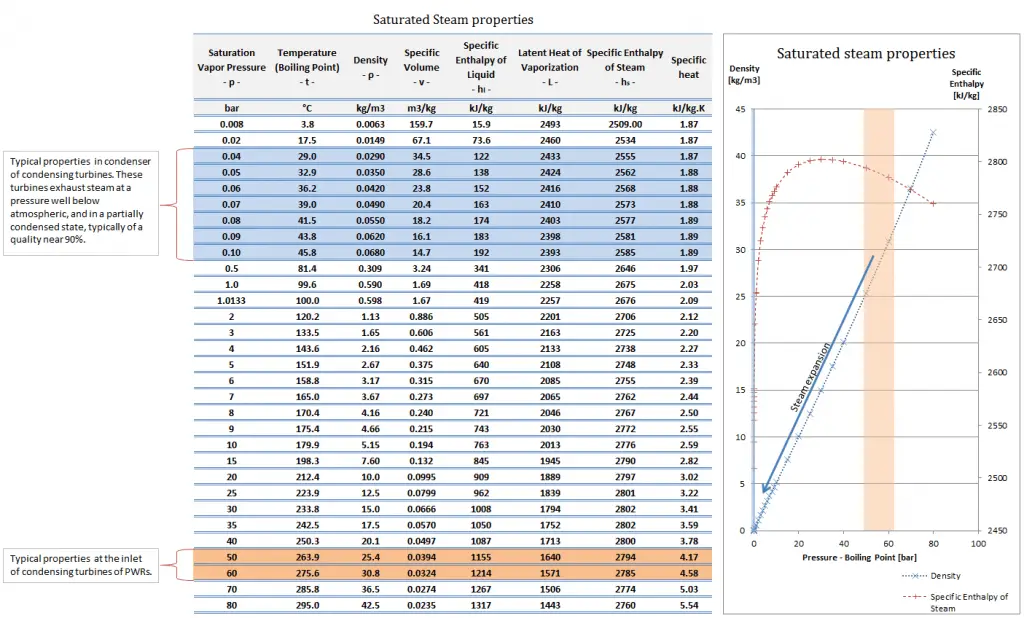

Water and steam are common medium because their properties are very well known. Their properties are tabulated in so-called “Steam Tables”. In these tables, the basic and key properties, such as pressure, temperature, enthalpy, density, and specific heat, are tabulated along the vapor-liquid saturation curve as a function of both temperature and pressure.

Water and steam are common medium because their properties are very well known. Their properties are tabulated in so-called “Steam Tables”. In these tables, the basic and key properties, such as pressure, temperature, enthalpy, density, and specific heat, are tabulated along the vapor-liquid saturation curve as a function of both temperature and pressure.

The density (⍴) of any substance is the reciprocal of its specific volume (ν).

ρ = m/V = 1/ν

The specific volume (ν) of a substance is the total volume (V) of that substance divided by the total mass (m) of that substance (volume per unit mass). It has units of cubic meters per kilogram (m3/kg).

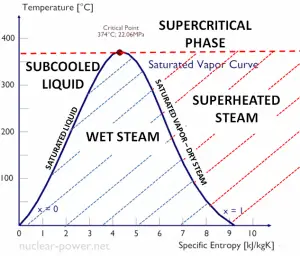

See also: Supercritical Fluid.

The density of Heavy Water

Pure heavy water (D2O) has a density about 11% greater than water but is otherwise physically and chemically similar.

The fact causes this difference, and the deuterium nucleus is twice as heavy as the hydrogen nucleus. Since about 89% of the molecular weight of water comes from the single oxygen atom rather than the two hydrogen atoms, the weight of a heavy water molecule is not substantially different from that of a normal water molecule. The molar mass of water is M(H2O) = 18.02, and the molar mass of heavy water is M(D2O) = 20.03 (each deuterium nucleus contains one neutron in contrast to the hydrogen nucleus). Therefore heavy water (D2O) has a density about 11% greater (20.03/18.03 = 1.112).

Pure heavy water (D2O) has its highest density of 1106 kg/m3 at a temperature of 11.6oC (52.9oF). Also, heavy water differs from most liquids in that it becomes less dense as it freezes. It has a maximum density of 11.6oC (1106 kg/m3), whereas its solid form ice density is 1017 kg/m3. It must be noted, the change in density is not linear with temperature because the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient for water is not constant over the temperature range.