What is Pressure

Pressure is a measure of the force exerted per unit area on the boundaries of a substance. The standard unit for pressure in the SI system is the Newton per square meter or pascal (Pa). Mathematically:

Pressure is a measure of the force exerted per unit area on the boundaries of a substance. The standard unit for pressure in the SI system is the Newton per square meter or pascal (Pa). Mathematically:

p = F/A

where

- p is the pressure

- F is the normal force

- A is the area of the boundary

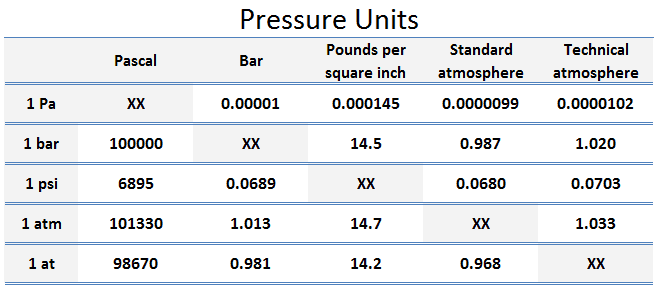

Pascal is defined as a force of 1N that is exerted on a unit area.

- 1 Pascal = 1 N/m2

- 1 MPa 106 N/m2

- 1 bar 105 N/m2

- 1 kPa 103 N/m2

In general, pressure or the force exerted per unit area on the boundaries of a substance is caused by the collisions of the molecules of the substance with the boundaries of the system. As molecules hit the walls, they exert forces that try to push the walls outward. The forces resulting from all of these collisions cause the pressure exerted by a system on its surroundings. Pressure as an intensive variable is constant in a closed system. It is only relevant in liquid or gaseous systems.

Bar – Unit of Pressure

A bar is a metric unit of pressure. It is not part of the International System of Units (SI). The bar is commonly used in the industry and meteorology, and an instrument used in meteorology to measure atmospheric pressure is called a barometer.

One bar is exactly equal to 100 000 Pa and is slightly less than the average atmospheric pressure on Earth at sea level (1 bar = 0.9869 atm). Atmospheric pressure is often given in millibars, where standard sea level pressure is defined as 1013 mbar, 1.013 bar, or 101.3 (kPa).

Sometimes, “Bar(a)” and “bara” are used to indicate absolute pressures, and “bar(g)” and “barg” for gauge pressures.

See also: Pascal – Unit of Pressure.

See also: Pound per square inch – psi.

See also: Typical Pressures in Engineering

Absolute vs. Gauge Pressure

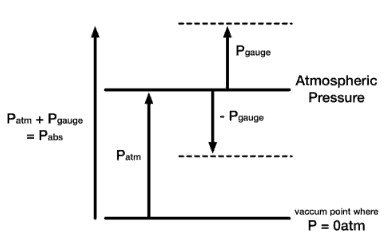

Pressure, as discussed above, is called absolute pressure. Often it will be important to distinguish between absolute pressure and gauge pressure. In this article, the term pressure refers to absolute pressure unless explicitly stated otherwise. But in engineering, we often deal with pressures that are measured by some devices. Although absolute pressures must be used in thermodynamic relations, pressure-measuring devices often indicate the difference between the absolute pressure in a system and the absolute pressure of the atmosphere existing outside the measuring device. They measure the gauge pressure.

Pressure, as discussed above, is called absolute pressure. Often it will be important to distinguish between absolute pressure and gauge pressure. In this article, the term pressure refers to absolute pressure unless explicitly stated otherwise. But in engineering, we often deal with pressures that are measured by some devices. Although absolute pressures must be used in thermodynamic relations, pressure-measuring devices often indicate the difference between the absolute pressure in a system and the absolute pressure of the atmosphere existing outside the measuring device. They measure the gauge pressure.

- Absolute Pressure. When pressure is measured relative to a perfect vacuum, it is called absolute pressure (psia). Pounds per square inch absolute (psia) is used to clarify that the pressure is relative to a vacuum rather than the ambient atmospheric pressure. Since atmospheric pressure at sea level is around 101.3 kPa (14.7 psi), this will be added to any pressure reading made in air at sea level.

- Gauge Pressure. When pressure is measured relative to atmospheric pressure (14.7 psi), gauge pressure (psig), the term gauge pressure is applied when the pressure in the system is greater than the local atmospheric pressure, patm. The latter pressure scale was developed because almost all pressure gauges register zero when open to the atmosphere. Gauge pressures are positive if they are above atmospheric pressure and negative if they are below atmospheric pressure.

pgauge = pabsolute – pabsolute; atm

- Atmospheric Pressure. Atmospheric pressure is the pressure in the surrounding air at – or “close” to – the surface of the Earth. The atmospheric pressure varies with temperature and altitude above sea level. The Standard Atmospheric Pressure approximates to the average pressure at sea-level at the latitude 45° N. The Standard Atmospheric Pressure is defined at sea-level at 273oK (0oC) and is:

- 101325 Pa

- 1.01325 bar

- 14.696 psi

- 760 mmHg

- 760 torr

- Negative Gauge Pressure – Vacuum Pressure. When the local atmospheric pressure is greater than the pressure in the system, the term vacuum pressure is used. A perfect vacuum would correspond to absolute zero pressure. It is certainly possible to have a negative gauge pressure but not possible to have negative absolute pressure. For instance, an absolute pressure of 80 kPa may be described as a gauge pressure of −21 kPa (i.e., 21 kPa below atmospheric pressure of 101 kPa).

pvacuum = pabsolute; atm – pabsolute

For example, a car tire pumped up to 2.5 atm (36.75 psig) above local atmospheric pressure (let say 1 atm or 14.7 psia locally), will have an absolute pressure of 2.5 + 1 = 3.5 atm (36.75 + 14.7 = 51.45 psia or 36.75 psig).

On the other hand condensing steam turbines (at nuclear power plants) exhaust steam at a pressure well below atmospheric (e.g., at 0.08 bar or 8 kPa or 1.16 psia) and in a partially condensed state. In relative units it is a negative gauge pressure of about – 0.92 bar, – 92 kPa, or – 13.54 psig.