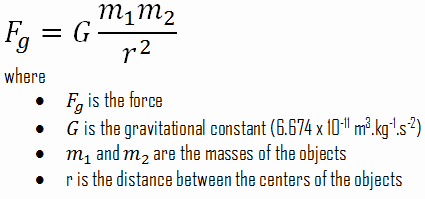

Gravity was the first force to be investigated scientifically. The gravitational force was described systematically by Isaac Newton in the 17th century. Newton stated that the gravitational force acts between all objects having mass (including objects ranging from atoms and photons to planets and stars) and is directly proportional to the masses of the bodies and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the bodies. Since energy and mass are equivalent, all forms of energy (including light) cause gravitation and are under its influence. The range of this force is ∞ , and it is weaker than the other forces. This relationship is shown in the equation below.

Gravitational Force – Formula

The equation illustrates that the larger the masses of the objects or the smaller the distance between the objects, the greater the gravitational force. So even though the masses of nucleons are very small, the fact that the distance between nucleons is extremely short may make the gravitational force significant. The gravitational force between two protons separated by a distance of 10-20 meters is about 10-24 newtons. Gravity is the weakest of the four fundamental forces of physics, approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong force. On the other hand, gravity is additive. Every speck of matter that you put into a lump contributes to the overall gravity of the lump. Since it is also a very long-range force, it is the dominant force at the macroscopic scale and is the cause of the formation, shape, and trajectory (orbit) of astronomical bodies.

The general theory of relativity is the fundamental theory of gravity. This theory describes gravity not as a force but as a consequence of the curvature of spacetime caused by the uneven distribution of mass. In theories of quantum gravity, the graviton is the hypothetical elementary particle that mediates the force of gravity.