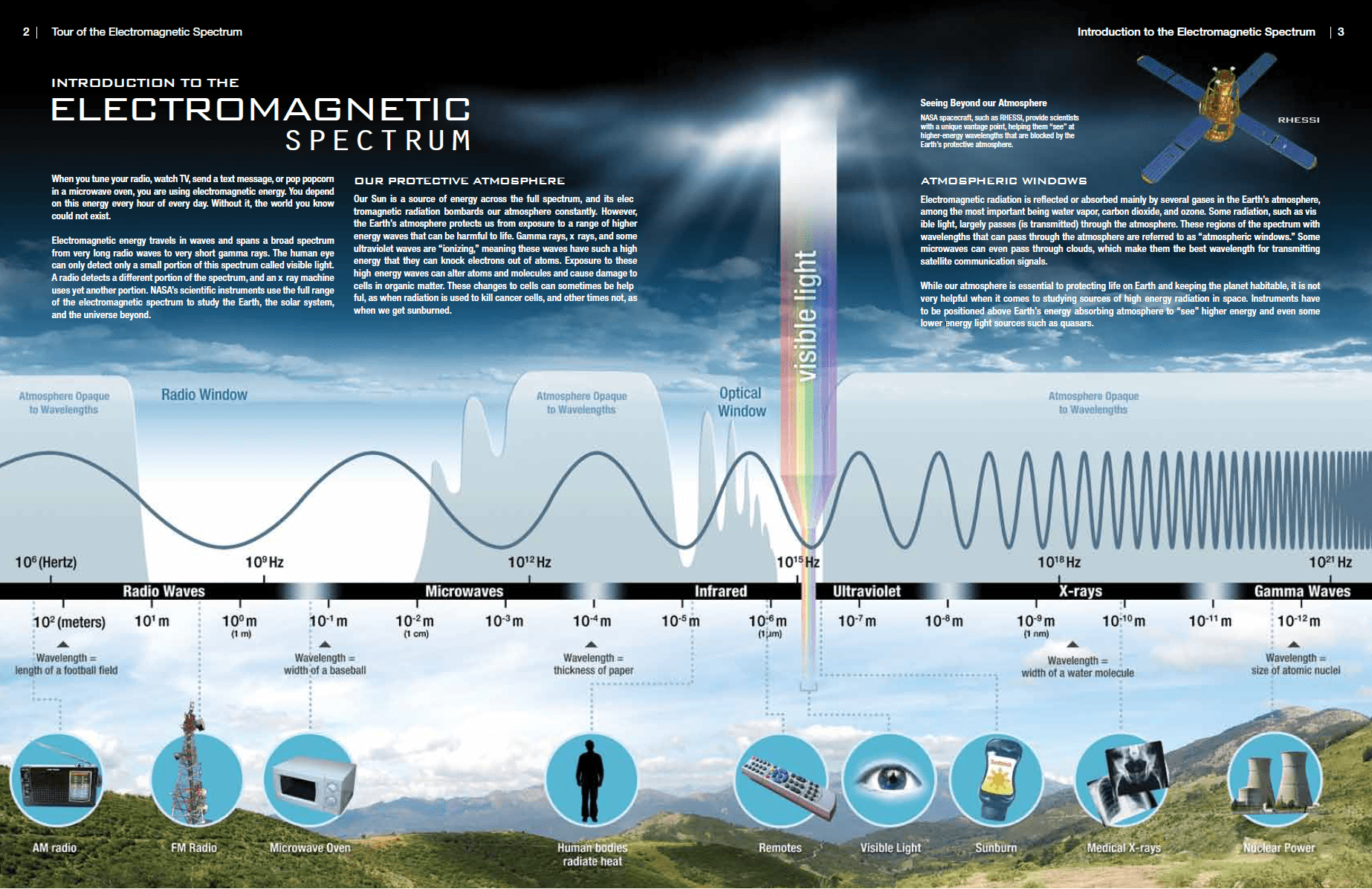

In general, electromagnetic radiation may be divided into visible and invisible portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Light is electromagnetic radiation within a certain portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. The word usually refers to visible light, the visible spectrum visible to the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths within the 400–700 nanometres (nm) range.

Electromagnetic radiation in the visible light region consists of quanta (called photons) at the lower end of the energies capable of causing electronic excitation within molecules, which leads to changes in the bonding or chemistry of the molecule. Photons are categorized according to their energies, from low-energy radio waves and infrared radiation, through visible light, to high-energy X-rays and gamma rays.

At the lower end of the visible light spectrum, electromagnetic radiation becomes invisible to humans (infrared) because its photons no longer have enough individual energy to cause a lasting molecular change (a change in conformation) in the visual molecule retinal in the human retina, which changes triggers the sensation of vision.

Invisible Radiation

All electromagnetic radiation except visible light (a narrow band) is invisible. Invisible radiation includes radio waves, infrared, UV, microwaves, and gamma radiation. In addition, alpha and beta radiation and “cathode rays” – all of which are streams of particles – are invisible.

Noteworthy neither invisible radiation is completely invisible to the human eye. A related topic is cosmic-ray visual phenomena, in which astronauts can see flashes of light, presumably due to individual cosmic-ray particles interacting with their eyes. Researchers believe these light flashes perceived specifically by astronauts in space are due to cosmic rays (high-energy charged particles from beyond the Earth’s atmosphere), though the exact mechanism is unknown.

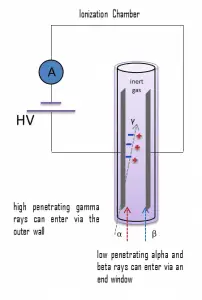

The danger of ionizing radiation lies in the fact that the radiation is invisible and not directly detectable by human senses. People can neither see nor feel radiation, yet it deposits energy into the material’s molecules. The energy is transferred in small quantities for each interaction between the radiation and a molecule, and there are usually many types of interactions. Therefore, the only way you can detect and measure radiation is to use instruments (detectors of ionizing radiation).

Detection of Invisible Radiation

Detectors of ionizing radiation consist of two parts that are usually connected. The first part consists of sensitive material, consisting of a compound that experiences changes when exposed to radiation. The other component is a device that converts these changes into measurable signals.

Detectors of ionizing radiation consist of two parts that are usually connected. The first part consists of sensitive material, consisting of a compound that experiences changes when exposed to radiation. The other component is a device that converts these changes into measurable signals.

In their basic operation principles, most ionizing radiation detectors follow similar characteristics. Detectors of ionizing radiation consist of two parts that are usually connected. The first part consists of sensitive material, consisting of a compound that experiences changes when exposed to radiation. The other component is a device that converts these changes into measurable signals. All detectors require that radiation deposit some of its energy in sensitive material that forms part of the instrument. The radiation enters the detector, interacts with atoms of the detector material, and deposits some energy into sensitive material. Each event may generate a signal, a pulse, hole, light signal, ion pairs in a gas, and many others. The main task is to generate a sufficient signal, amplify it, and record it.