The radioactive decay of a certain number of atoms (mass) is exponential in time.

Radioactive decay law: N = N.e-λt

The rate of nuclear decay is also measured in terms of half-lives.

The radioactive decay law can also be derived for activity calculations or mass of radioactive material calculations:

(Number of nuclei) N = N.e-λt (Activity) A = A.e-λt (Mass) m = m.e-λt

where N (number of particles) is the total number of particles in the sample, A (total activity) is the number of decays per unit time of a radioactive sample, and m is the mass of remaining radioactive material.

The radioactive decay law states that the probability per unit time that a nucleus will decay is a constant, independent of time. This constant is called the decay constant and is denoted by λ, “lambda.” This constant probability may vary greatly between different types of nuclei, leading to the many different observed decay rates. The radioactive decay of a certain number of atoms (mass) is exponential in time.

Radioactive decay law: N = N.e-λt

The rate of nuclear decay is also measured in terms of half-lives. The half-life is the time it takes for a given isotope to lose half of its radioactivity. If a radioisotope has a half-life of 14 days, half of its atoms will have decayed within 14 days. In 14 more days, half of that remaining half will decay, and so on. Half-lives range from millionths of a second for highly radioactive fission products to billions of years for long-lived materials (such as naturally occurring uranium). Notice that short half-lives go with large decay constants. Radioactive material with a short half-life is much more radioactive (at the time of production) but will obviously lose its radioactivity rapidly. No matter how long or short the half-life is after seven half-lives have passed, there is less than 1 percent of the initial activity remaining.

The radioactive decay law can be derived also for activity calculations or mass of radioactive material calculations:

(Number of nuclei) N = N.e-λt

(Activity) A = A.e-λt

(Mass) m = m.e-λt

where N (number of particles) is the total number of particles in the sample, A (total activity) is the number of decays per unit time of a radioactive sample, and m is the mass of remaining radioactive material.

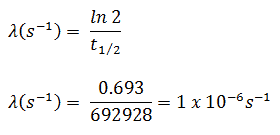

Decay Constant and Half-Life – Equation – Formula

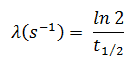

In radioactivity calculations, one of two parameters (decay constant or half-life), which characterize the decay rate, must be known. There is a relation between the half-life (t1/2) and the decay constant λ. The relationship can be derived from the decay law by setting N = ½ No. This gives:

where ln 2 (the natural log of 2) equals 0.693. If the decay constant (λ) is given, it is easy to calculate the half-life and vice-versa.

where ln 2 (the natural log of 2) equals 0.693. If the decay constant (λ) is given, it is easy to calculate the half-life and vice-versa.

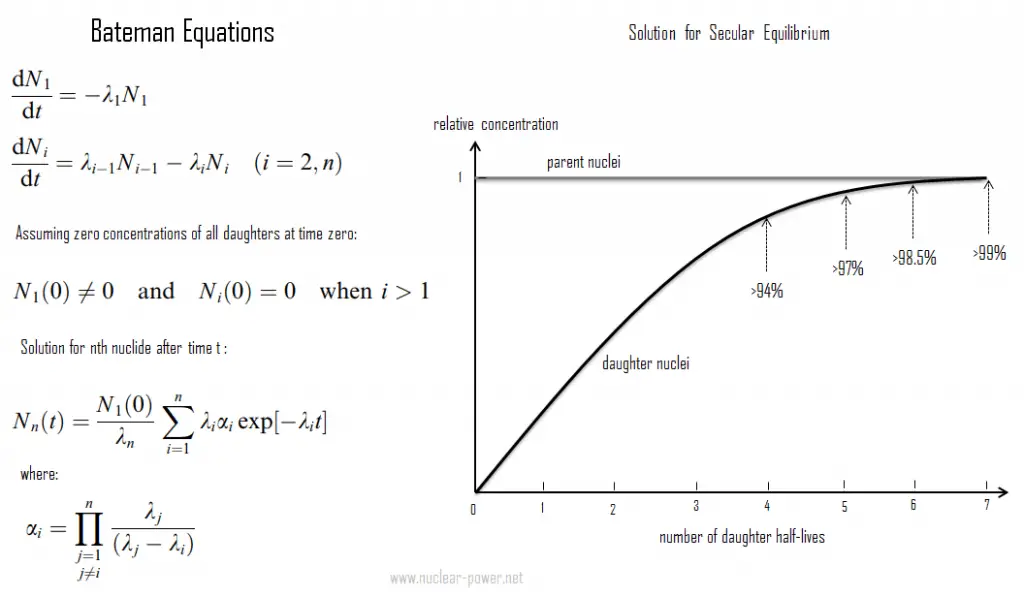

Bateman Equations

In physics, the Bateman equations are a set of first-order differential equations which describe the time evolution of nuclide concentrations undergoing serial or linear decay chain. Ernest Rutherford formulated the model in 1905, and the analytical solution for the case of radioactive decay in a linear chain was provided by Harry Bateman in 1910. This model can also be used in nuclear depletion codes to solve nuclear transmutation and decay problems.

For example, ORIGEN is a computer code system for calculating radioactive materials’ buildup, decay, and processing. ORIGEN uses a matrix exponential method to solve a large system of coupled, linear, first-order ordinary differential equations (similar to the Bateman equations) with constant coefficients.

The Bateman equations for radioactive decay case of n – nuclide series in linear chain describing nuclide concentrations are as follows:

Example – Radioactive Decay Law

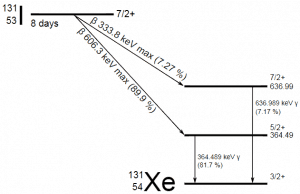

A sample of material contains 1 microgram of iodine-131. Note that iodine-131 plays a major role as a radioactive isotope present in nuclear fission products and is a major contributor to the health hazards when released into the atmosphere during an accident. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8.02 days.

A sample of material contains 1 microgram of iodine-131. Note that iodine-131 plays a major role as a radioactive isotope present in nuclear fission products and is a major contributor to the health hazards when released into the atmosphere during an accident. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8.02 days.

Calculate:

- The number of iodine-131 atoms is initially present.

- The activity of the iodine-131 in curies.

- The number of iodine-131 atoms will remain in 50 days.

- The time it will take for the activity to reach 0.1 mCi.

Solution:

- The number of atoms of iodine-131 can be determined using isotopic mass as below.

NI-131 = mI-131 . NA / MI-131

NI-131 = (1 μg) x (6.02×1023 nuclei/mol) / (130.91 g/mol)

NI-131 = 4.6 x 1015 nuclei

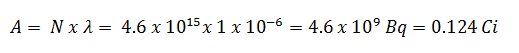

- The activity of the iodine-131 in curies can be determined using its decay constant:

The iodine-131 has a half-life of 8.02 days (692928 sec), and therefore its decay constant is:

Using this value for the decay constant, we can determine the activity of the sample:

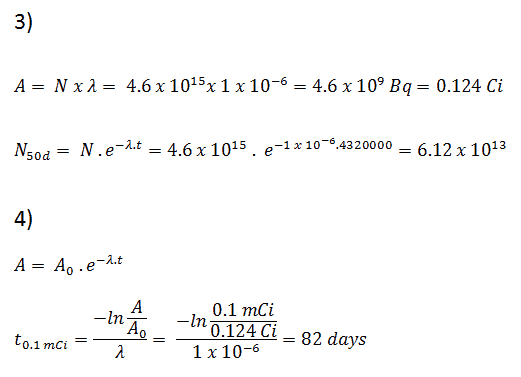

3) and 4) The number of iodine-131 atoms that will remain in 50 days (N50d) and the time it will take for the activity to reach 0.1 mCi can be calculated using the decay law:

As can be seen, after 50 days, the number of iodine-131 atoms and thus the activity will be about 75 times lower. After 82 days, the activity will be approximately 1200 times lower. Therefore, the time of ten half-lives (factor 210 = 1024) is widely used to define residual activity.