The neutron flux can have any value, and the critical reactor can operate at any power level. It should be noted the flux shape derived from the diffusion theory is only a hypothetical case in a uniform homogeneous cylindrical reactor at low power levels (at “zero power criticality”).

In the power reactor core at power operation, the neutron flux can reach, for example, about 3.11 x 1013 neutrons.cm-2.s-1, but this value depends significantly on many parameters (type of fuel, fuel burnup, fuel enrichment, position in fuel pattern, etc.). The power level does not influence the criticality (keff) of a power reactor unless thermal reactivity feedbacks act (operation of a power reactor without reactivity feedbacks is between 10E-8% – 1% of rated power).

At power operation (i.e., above 1% of rated power), the reactivity feedbacks cause the flattening of the flux distribution because the feedbacks acts stronger on positions where the flux is higher. The neutron flux distribution in commercial power reactors depends on many other factors such as the fuel loading pattern, control rods position, and it may also oscillate within short periods (e.g.,, due to the spatial distribution of xenon nuclei). There is no cosine and J0 in the commercial power reactor at power operation.

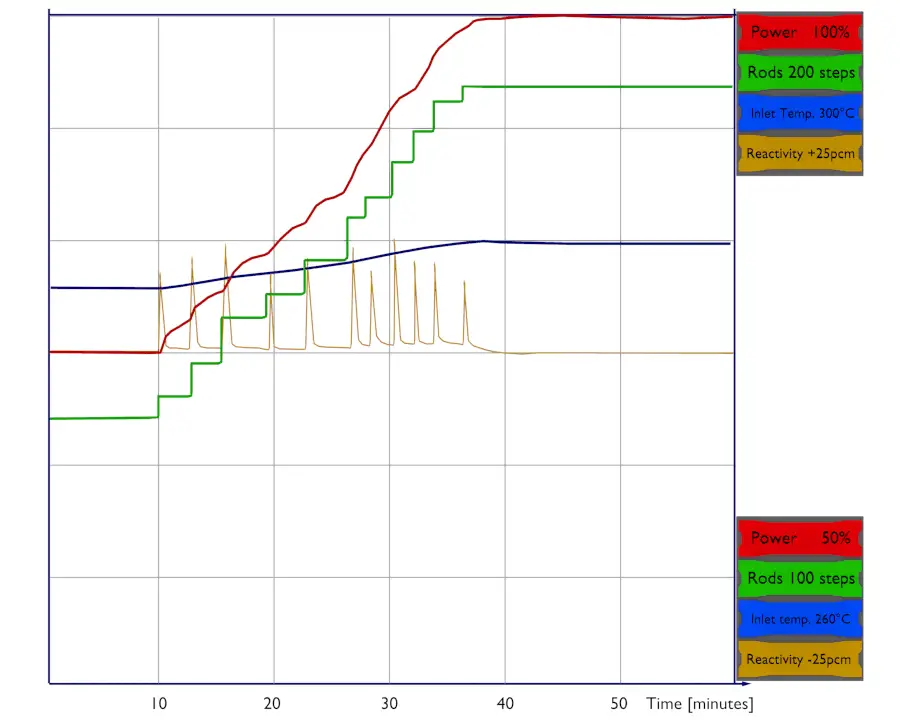

Example: Power increase – from 75% up to 100%

The temperature, pressure, or void fraction change during any power increase, and the core’s reactivity changes accordingly. It is difficult to change any operating parameter and not affect every other property of the core. Since it is difficult to separate all these effects (moderator, fuel, void, etc.), the power coefficient is defined. The power coefficient combines the Doppler, moderator temperature, and void coefficients. It is expressed as a change in reactivity per change in percent power, Δρ/Δ% power. The value of the power coefficient is always negative in core life. Still, it is more negative at the end of the cycle primarily due to the decrease in the moderator temperature coefficient.

Let us assume that the reactor is critical at 75% of rated power and that the plant operator wants to increase power to 100% of rated power. The reactor operator must first bring the reactor supercritical by inserting a positive reactivity (e.g.,, by control rod withdrawal or boron dilution). As the thermal power increases, moderator temperature and fuel temperature increase, causing a negative reactivity effect (from the power coefficient), and the reactor returns to the critical condition. Positive reactivity must be continuously inserted (via control rods or chemical shim) to keep the power increasing. After each reactivity insertion, the reactor power stabilizes itself proportionately to the reactivity inserted. The total amount of feedback reactivity that must be offset by control rod withdrawal or boron dilution during the power increase (from ~1% – 100%) is known as the power defect.

Let assume:

- the power coefficient: Δρ/Δ% = -20pcm/% of rated power

- differential worth of control rods: Δρ/Δstep = 10pcm/step

- worth of boric acid: -11pcm/ppm

- desired trend of power decrease: 1% per minute

75% → ↑ 20 steps or ↓ 18 ppm of boric acid within 10 minutes → 85% → next ↑ 20 steps or ↓ 18 ppm within 10 minutes → 95% → final ↑ 10 steps or ↓ 9 ppm within 5 minutes → 100%