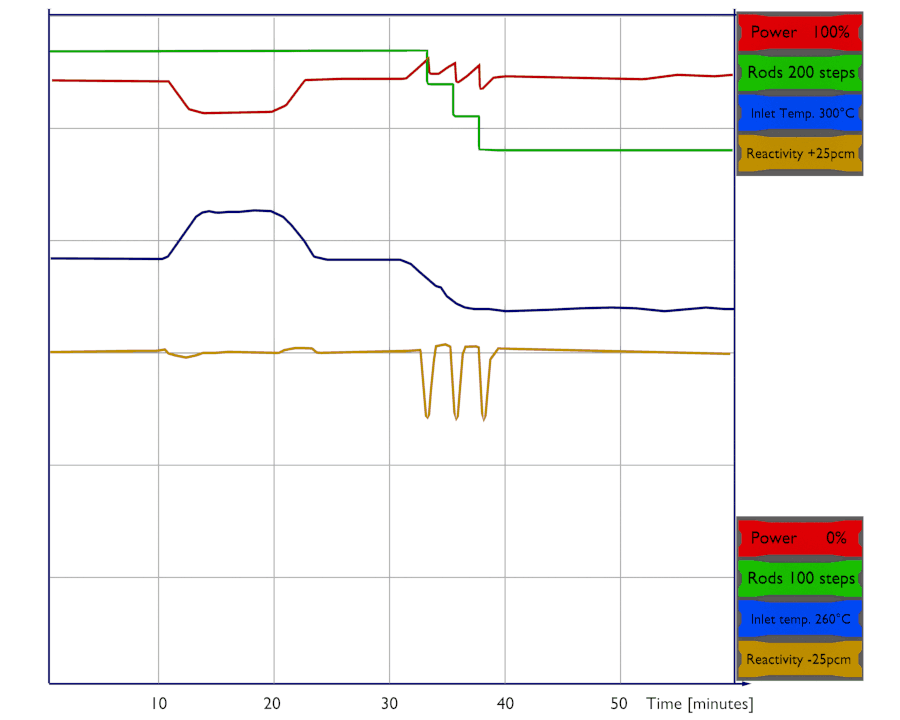

The fuel temperature coefficient – FTC or DTC is defined as the change in reactivity per degree change in the fuel temperature.

αf = dρ⁄dTf

It is expressed in units of pcm/°C or pcm/°F. The magnitude and sign (+ or -) of the fuel temperature coefficient is primarily a function of the fuel composition, especially the fuel enrichment. In power reactors, in which low enriched fuel (e.g.,, PWRs and BWRs require 3% – 5% of 235U) is used, the Doppler coefficient is always negative. The value of the Doppler coefficient αf depends on the fuel’s temperature and depends on the fuel burnup. In PWRs, the Doppler coefficient can range, for example, from -5 pcm/°C to -2 pcm/°C.

This coefficient is of the highest importance in reactor stability. The fuel temperature coefficient is generally considered even more important than the moderator temperature coefficient (MTC). Especially in the case of all reactivity-initiated accidents (RIA), the fuel temperature coefficient will be the first and the most important feedback that will compensate for the inserted positive reactivity. The time for heat to be transferred to the moderator is usually measured in seconds, while the fuel temperature coefficient is effective almost instantaneously.

Therefore this coefficient is also called the prompt temperature coefficient because it causes an immediate response to changes in fuel temperature.

Since the phenomenon, which is dominantly responsible for the fuel temperature coefficient, is the Doppler broadening of resonances, it is also known as the Doppler coefficient. The Doppler broadening of resonances is a very important phenomenon, which improves reactor stability.

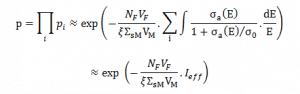

The total amount of reactivity, which is inserted to a reactor core by a specific change in the fuel temperature, is usually known as the doppler defect and is defined as:

dρ = α . dT

Theory of Doppler Coefficient

↑Tf ⇒ ↓keff = η.ε. ↓p .f.Pf .Pt

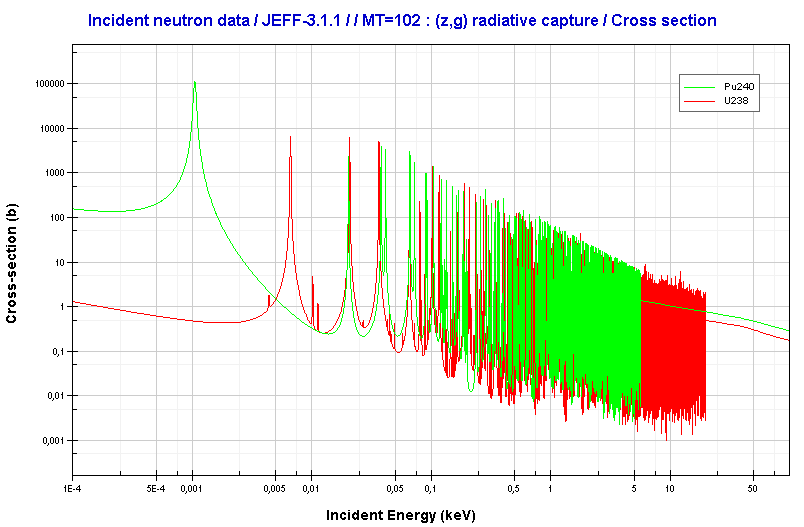

Change in the fuel temperature affects primarily the resonance escape probability via the thermal Doppler broadening of the resonance capture cross-sections of the fertile material (e.g.,, 238U or240Pu) caused by the thermal motion of target nuclei in the nuclear fuel.

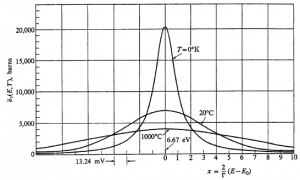

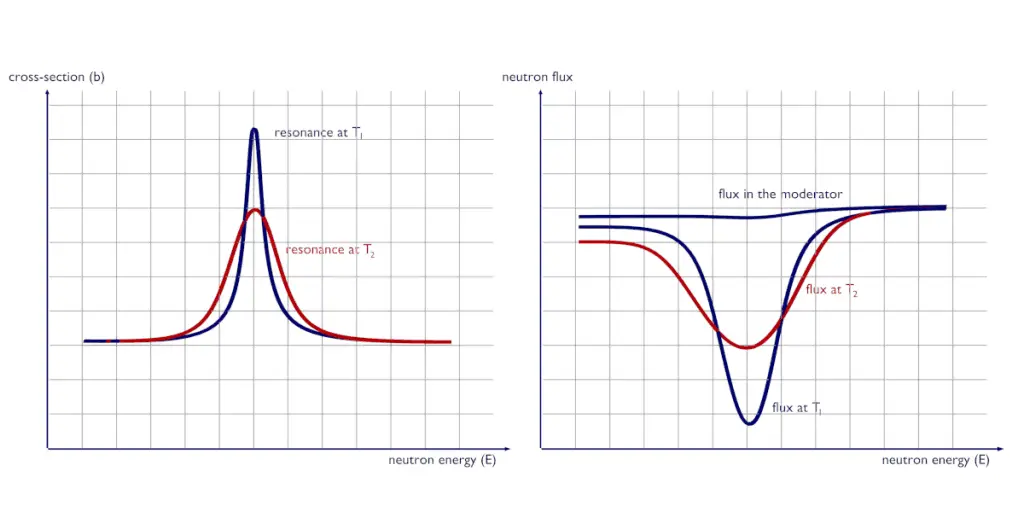

The Doppler effect arises from the dependence of neutron cross sections on the relative velocity between neutron and nucleus. The probability of the radiative capture depends on the center-of-mass energy. Therefore, it depends on the kinetic energy of the incident neutron and the velocity of the target nucleus. Target nuclei are themselves in continual motion owing to their thermal energy. As a result of these thermal motions, neutrons impinging on a target appear to the target’s nuclei to have a continuous spread in energy. This, in turn, affects the observed shape of resonance. Raising the temperature causes the nuclei to vibrate more rapidly within their lattice structures, effectively broadening the energy range of neutrons that may be resonantly absorbed in the fuel. The resonance becomes shorter and wider than when the nuclei are at rest.

Although the shape of a resonance changes with temperature, the total area under the resonance remains essentially constant. But this does not imply constant neutron absorption. Despite the constant area under resonance, the resonance integral, which determines the absorption, increases with increasing target temperature. The broadened resonances result in a larger percentage of neutrons having energies susceptible to capture in the fuel pellets. On the other hand, only neutrons very close to the resonance energy are absorbed with colder fuel.

Moreover, there is a further phenomenon closely connected with Doppler broadening. The vicinity of the resonance causes an increase in the neutron absorption probability when a neutron has energy near a resonance. This results in a reduction of the effective absorption per nucleus due to the depression of the energy-dependent flux Φ(E) near the resonance in comparison to a flat flux. At energies just below the resonance, where Σa(E) becomes small again, the neutron flux reaches almost the same value above the resonance. This reduction in the energy-dependent neutron flux near the resonance energy is known as energy self-shielding. These two phenomena provide negative reactivity feedback against fuel temperature increase.

Doppler Coefficient in Power Reactors

In power reactors, the Doppler coefficient is always negative. The fuel composition ensures it. In PWRs, the Doppler coefficient can range, for example, from -5 pcm/K to -2 pcm/K. The value of the Doppler coefficient αf depends on the fuel’s temperature and depends on the fuel burnup.

- Fuel Temperature. The dependency on the fuel temperature is determined by the fact the rate of broadening diminishes at higher temperatures. Therefore the Doppler coefficient becomes less negative (but always remains negative) as the reactor core heats up.

- Fuel-cladding gap. There is also one very important phenomenon, which influences the fuel temperature. As the fuel burnup increases, the fuel-cladding gap reduces. This reduction is caused by the swelling of the fuel pellets and cladding creep. Fuel pellets swelling occurs because fission gases cause the pellet to swell, resulting in a larger pellet volume. At the same time, the cladding is distorted by outside pressure (known as the cladding creep). These two effects result in direct fuel-cladding contact (e.g.,, at burnup of 25 GWd/tU). The direct fuel-cladding contact causes a significant reduction in fuel temperature profile because the overall thermal conductivity increases due to conductive heat transfer.

- Fuel Burnup. During fuel burnup, the fertile materials (conversion of 238U to fissile 239Pu known as fuel breeding) partially replace fissile235U. The plutonium content raises with the fuel burnup. For example, at a burnup of 30 GWd/tU (gigawatt-days per metric ton of uranium), about 30% of the total energy released comes from bred plutonium. But with the 239Pu also raises the content of 240Pu, which has significantly higher resonance cross-sections than 238U. Therefore the Doppler coefficient becomes more negative as the 240Pu content raises.

In summary, it is difficult to define the depedency, because these effects have opposite directions.

Doppler Coefficient in Fast Reactors

In fast neutron reactors, the Doppler effect becomes less dominant (due to the minimization of the neutron moderation) but strongly depends on the neutron spectrum (e.g.,, gas-cooled reactors have harder spectra than other fast reactors) and the type of the fuel matrix (metal fuel, ceramic fuel, etc.)

In fast reactors, other effects, such as the axial thermal expansion of fuel pellets or the radial thermal expansion of reactor core, may also contribute to the fuel temperature coefficient. In thermal reactors, these effects tend to be small relative to that of Doppler broadening.

Fuel Temperature Coefficient and Fuel Design

In general, the fuel temperature coefficient is primarily a function of the fuel enrichment. There are two phenomena associated with the Doppler effect. It results in increased neutron capture by fuel nuclei (both fissile and fissionable) in the resonance region. On the other hand, it results in increased neutron production from fissile nuclei. Therefore DTC may also be positive. A net positive Doppler coefficient requires higher enrichments of fissile nuclei. Some calculations show that enrichments higher than 30% are associated with slightly positive DTC, but this enrichment results in a harder neutron spectrum. Low enriched uranium oxide fuels usually provide a large negative DTC because of the elastic scattering reaction of oxygen nuclei (soften spectrum). Another way to produce more negative DTC is to soften the neutron spectrum by adding moderator nuclei directly into the fuel matrix. For example, the TRIGA reactor uses uranium zirconium hydride (UZrH) fuel, which has a large negative fuel temperature coefficient. The rise in temperature of the hydride increases the probability that a thermal neutron in the fuel element will gain energy from an excited state of an oscillating hydrogen atom in the lattice as the neutrons gain energy from the ZrH, the thermal neutron spectrum in the fuel element shifts to higher average energy (i.e., the spectrum is hardened). This spectrum hardening is used differently to produce the negative temperature coefficient.

In the United States, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission will not license a reactor unless αPrompt (FTC) is negative. All licensed reactors are thereby assured of being inherently stable. This requirement is followed by many other countries.