In nuclear safety, the source term refers to the magnitude and mix of the radionuclides released from the fuel and reactor coolant, which would be available for escape to the environment from a nuclear reactor that has undergone a severe accident.

Source term is a very important part of reactor safety analysis. In principle, the reactor accidents that could have the largest source term for a given LWR plant are those in which severe fuel damage occurs in addition to one of three classes of containment impairment.

The accidents are those that:

- might threaten containment integrity early in the history of the event;

- might remobilize large amounts of fission products in late containment failure;

- might lead to a bypass of the containment function.

Radioactive material escaping from the containment is often referred to as the “radiological release to the environment.” The radiological release is obtained from the containment leak rate and knowledge of the airborne radioactive inventory in the containment atmosphere. The radioactive inventory within containment is referred to as the “in-containment accident source term.”

For all accidents with the potential for release of radioactivity into the environment, the class of accidents that had the shortest time until the first fuel rod failed was the design basis LOCA. As might be expected, the time until cladding failure is very sensitive to the reactor’s design, the type of accident assumed, and the fuel rod design. In particular, the maximum linear heat generation rate, the internal fuel rod pressure, and the stored energy in the fuel rod are significant considerations.

The most important ways to maintain risk and the source term at low levels are design features and accident management methods that would prevent severe core damage. The next most important are design features and accident management methods that would preserve the containment’s integrity and functions.

For analysis of the source term, specific groupings of postulated initiating events may be appropriate to adequately address different pathways that could lead to releasing radioactive material into the environment. Special attention should be paid to accidents in which the release of radioactive material could bypass the containment because of the potentially severe consequences, even in the case of relatively small releases.

Radionuclides of greatest concern in reactor safety

The radionuclides in a nuclear reactor that could most affect public health if released are the fission products and the actinides produced by neutron transmutation. It must be noted that irradiated nuclear fuel contains many different isotopes that contribute to radiological hazards. Fission fragments with a short half-life are much more radioactive (at the time of production) and contribute significantly to local hazards, but will obviously lose their share rapidly. On the other hand, fission fragments and transuranic elements with a long half-life are less radioactive (at the time of production) and produce acute hazards but will obviously lose their share more slowly. In considering the hazards of these radionuclides released in an accident sequence, many factors determine their importance, and these are especially:

- Core inventory. Core inventory (i.e., total activity) depends on the balance between formation and decay.

- Chemical and physical properties. The chemical and physical properties of radionuclides determine cumulation and various reactions that may occur during accidents, which could affect the transport and absorption of radionuclides after their release.

- Biological characteristics. Radioactive isotopes that were ingested or taken in through other pathways will gradually be removed from the body via bowels, kidneys, respiration, and perspiration. This means that a radioactive substance can be expelled before it has had the chance to decay.

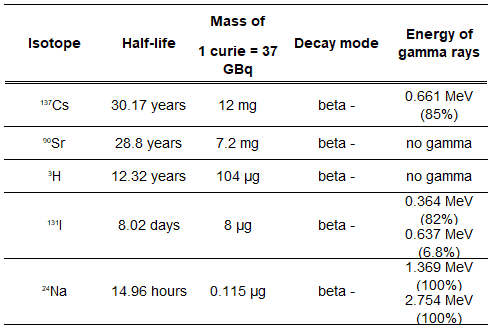

Radionuclides of greatest concern in reactor safety are summarized in the table, and these are:

- Iodine-131. I-131 decays with a half-life of 8.02 days with beta particle and gamma emissions. As it decays, it may cause damage to the thyroid. The primary risk from exposure to high levels of I-131 is the chance occurrence of radiogenic thyroid cancer in later life. For I-131, ICRP has calculated that if you inhale 1 x 106 Bq, you will receive a thyroid dose of HT = 400 mSv (and a weighted whole-body dose of 20 mSv).

- Strontium-90. Sr-90, Ra-226, and Pu-239 are radionuclides known as bone-seeking radionuclides. These radionuclides have long biological half-lives and are serious internal hazards. Once deposited in bone, they remain essentially unchanged in amount during the individual’s lifetime.

- Caesium-137. Caesium-137 is among the most problematic short-to-medium-lifetime fission products because it easily moves and spreads in nature due to its high water solubility. The biological behavior of cesium is similar to that of potassium.

- Tritium. Tritium emits low-energy beta particles with a short range in body tissues and, therefore, poses a risk to health due to internal exposure only following ingestion in drinking water or food, or inhalation or absorption through the skin. The tritium taken into the body is uniformly distributed among all soft tissues. According to the ICRP, a biological half-time of tritium is 10 days for HTO and 40 days for OBT (organically bound tritium) formed from HTO in the body of adults. As a result, for an intake of 1 x 109 Bq of tritium (HTO), an individual will get a whole-body dose of 20 mSv.

See also: Dangerous quantities of radioactive material (D-values), EPR-D-VALUES 2006. IAEA 2006